Once, Students in the US Were Punished for Speaking Spanish. Here, They Are Honored.

Kiara Rivas-Vasquez, a sixth-grader from Oregon, gives a confident smile to her mother who is watching on from the front row. Credit: Simon Thompson/PRI

This article by Simon Thompson originally appeared on PRI.org on July 27, 2016. It is republished here as part of a content-sharing agreement.

The amphitheater is humming: teachers hover, students murmur over spelling sheets and proud parents deliver the last gasps of pep talks. After final embraces and a tear or two, the spelling competitors are swept backstage.

It is sixth grader Jybr Reynoso Hidrogos’ second time competing. He made the top five last year, but fell short of a trophy. Every day since, he’s spent two hours or more practicing spelling. That’s what helped him beat out his classmates and win a preliminary contest to wind up here today.

“It seemed impossible and I am actually here. It is like a dream,” Jybr says.

This isn’t the Scripps National Spelling Bee that you watch on ESPN. This is Concurso Nacional de Deletreo en Español, the National Spanish Spelling Bee, held this month in San Antonio, Texas.

Words are drawn from the “Lista de Palabras,” a 1,448-long list of Spanish words. When contestants need a word repeated, defined or used in a sentence, they are encouraged to ask the judges in Spanish. They also have to correctly place any diacritical marks, like the tilde in artimaña (trick), the dieresis in ungüento (ointment) or the accent in constelación (constellation).

“It makes it hard sometimes,” says Jybr. “There some words where it seems like there is no accent — maybe you can’t hear it — but actually it is there.”

Jybr has been learning Spanish from the cradle. Though he is in the bilingual track at Bradley Middle School in San Antonio’s North East Independent School District, he mainly speaks English with his school friends.

His parents came to the US from Mexico before he was born. His father, Liborio Reynoso, says seeing his son compete in their native language is a massive point of pride.

“Oh man!” he says. “My first language, my native language. We want our language to grow up here in this country.”

It wasn’t that long ago that first-generation American citizens like Jybr were scolded for speaking Spanish at school and encouraged to abandon their native language.

The director of the Spanish spelling bee, David Briseño, grew up in the US state of New Mexico where his Spanish-speaking parents were convinced that teaching their children the language would hold them back. Now 60, he says he still hasn’t quite mastered Spanish.

“My parents went through the time when you were punished in school for speaking Spanish,” he says. “They wanted to make sure we weren’t getting punished.”

His parents, he says, were belittled, spanked or could have their mouths washed out with soap if teachers caught them speaking their native language. Many people don’t like to talk about this painful history, but another school administrator at the spelling bee tells me the same thing happened to her parents. At last year’s bee, José Reyes, a bilingual instructor from Gadsden Independent School District in New Mexico, told me that a teacher punished him for speaking in Spanish. He went to school in El Paso, Texas, in the 1960s and 70s.

“I used Spanish and I remember her taking me to the sink in the corner and washed my mouth with Borax, with soap. And she said, ‘You won’t use this language again.’”

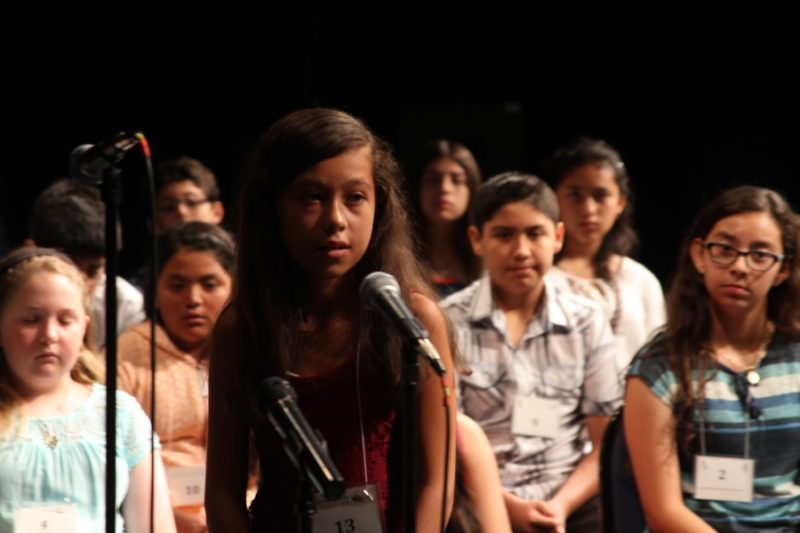

Fifth-grader Mariana Moya-Rubiano from Thomas Harrison Middle School, Harrisburg, Virginia, correctly spells her first word in the competition. 27 students competed — accents, tildes and all — in the bee this year. Credit: Simon Thompson/PRI

Briseño founded the National Spanish Spelling Bee six years ago to change these attitudes and to raise the status of the Spanish language in the US.

Efforts like his are making a difference. The benefits of bilingual learning gained Once, Students in the US Were Punished for Speaking Spanish. Here, They Are Honored. · Global Voices: