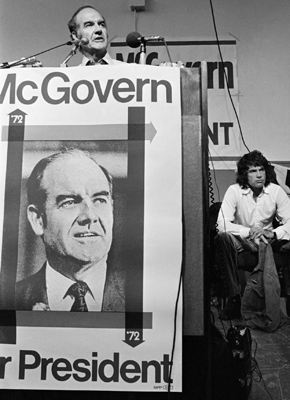

The highest patriotism is not a blind acceptance of official policy, but a love of one's country deep enough to call her to a higher plain.

George McGovern

Nixonland

An unpopular war, an economy in the dumps, a President with low approval ratings, his opponent revitalizing his base: How did the democrats lose in 1972, and by a historic margin?

RICK PERLSTEIN

Democrats started straggling into Miami Beach the second week in July, 1972. One of them was Robert Redford, arriving by train, promoting 'The Candidate' on a mock whistle-stop tour. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin set up housekeeping at the run-down Albion Hotel, where Rita Hayworth and Orson Welles once honeymooned. Everywhere, Hoffman and Rubin were mobbed by cops hoping to make it into the documentary that rumor had it Warner's had paid them millions to shoot. They wouldn't be doing much in the way of protesting, they promised, so long as the nomination wasn't stolen from McGovern. "McGovern Backer No Longer Thinks Sons, Daughters, Should Kill Parents," the RNC magazine First Monday headlined an interview with Rubin. Only tiny left-wing splinter groups considered McGovern the enemy.

Yippies met with Miami Beach's glad-handing liberal police chief, who laid out the ground rules: "Fellas, I don't believe in trying to enforce laws that can't be enforced. If you guys smoke a little pot, I'm not going to send my men in after you." They got the same welcome from Mayor Charles Hall. "Call me Chuck," he said, before showing off his print of John and Yoko's wedding day—"It's the original, you know"—and offering them the city's golf courses as campsites. When the Yippies staged their first march to the convention center, "Chuck" arrived to try to lead it. Abbie and Jerry were celebrities. Celebrity was power in 1972. Abbie and Jerry were all about the new youth vote. Youth was power, too.

At McGovern headquarters at the famous Doral resort, the usual haunt of golfing Shriners, hordes of kids awaited their hero's arrival, "wearing," Norman Mailer wrote, "copper