San Bernardino County pay the price with overzealous school cops

San Bernardino school police arrested more kids than cops in Sacramento, Oakland or San Francisco. What gives?

SAN BERNARDINO, Calif. — Josue “Josh” Muniz admits that he embraced his girlfriend during lunch, while the pair was out on the quad at Arroyo Valley High School in this city east of Los Angeles.

He admits that after a school cop ordered him to step away, he did, but lightly hugged his girlfriend again, minutes later, because she was upset.

But Muniz won’t agree that he deserved what happened next.

His girlfriend walked off, and Muniz saw the officer approaching again and directing him to go with him. The cop reached out and “put his hand on my throat,” Muniz said. “That’s when I start freaking out. He tells me to stand up. And that’s when his grip on my throat got a little stronger and when I started really panicking.”

Alarmed, Muniz pushed at the officer to get him “just a little bit off me,” he said. They tumbled to the ground and the officer “showered” the student with pepper spray, Muniz alleges in a civil lawsuit that’s still pending. The cop handcuffed him, he said, dragged him into a nearby security office by the cuffs and planted a knee in between his shoulder blades while delivering “multiple blows” as Muniz lay face down on a carpet.

After it was over, the officer read the 17-year-old junior his rights and placed Muniz under arrest — for alleged misdemeanor assault on an officer.

“He told me that I had ‘f’d up,’” Muniz said. “But I never wanted to fight.”

In an initial substantive response in court, the school district claims that Muniz was “careless, reckless, and negligent,” and is the one to blame for any alleged injuries he suffered during the altercation.

Muniz’s arrest in November 2012 sounds extreme, but it was hardly isolated.

In fact, he was one of tens of thousands of juveniles arrested by school police in San Bernardino County over the last decade. The arrests were so numerous in this high-desert region known as the Inland Empire that they surpassed arrests of juveniles by municipal police in some of California’s biggest cities.

The San Bernardino City Unified School District, where Muniz was a student, has its own police department, with 28 sworn officers, eight support staff and more than 50 campus security officers trained in handcuffing and baton use.

The department made more than 30,000 arrests of minors between 2005 and 2014. The area has a reputation for youth-gang crime, but only about 9 percent of those arrests were for alleged felonies. Instead, the vast majority of arrests were for minors violating a variety of city ordinances — such as graffiti violations or daytime curfews — and for nearly 9,900 allegations of disturbing the peace. That’s a frequently-used catchall that raises questions among critics about whether most of these arrests were necessary for public safety.

The bulk of the minors arrested or referred to school police represent some of the most academically vulnerable demographics in the state: low-income Latino and black kids, as well as kids with disabilities, in disproportionate numbers, according to California arrest statistics and national education data examined by the Center for Public Integrity.

Based on 2011-2012 data collected from U.S. schools by the U.S. Department of Education, the latest available, Muniz’s Arroyo Valley High referred students to law enforcement at a rate of 65 for every 1,000 students. That was more than 10 times the national and California state rate of 6 per 1,000.

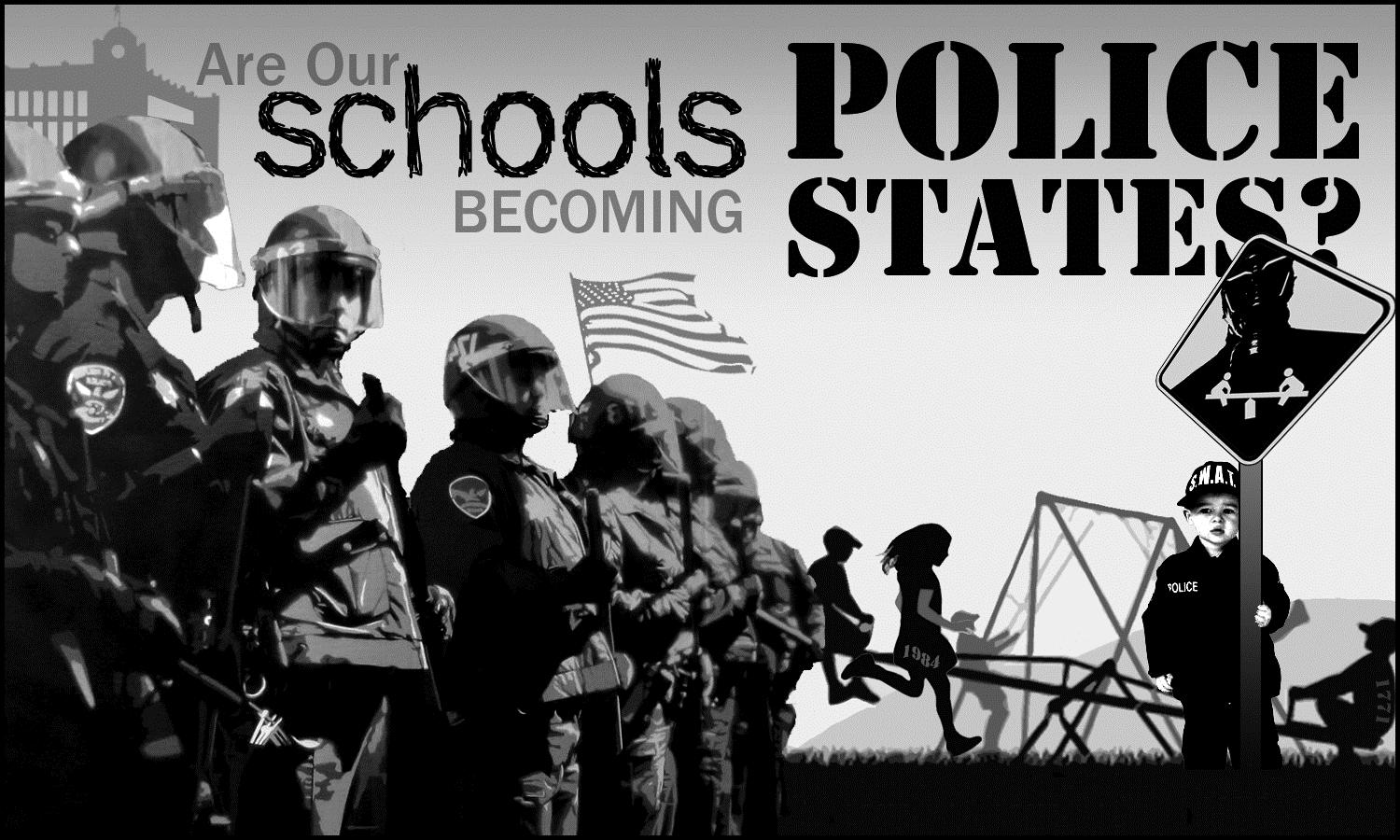

Those kinds of statistics raise red flags for critics who charge that school officers in some districts, especially those with substantial minority and special-needs populations, are turning what should be minor disciplinary indiscretions into criminal justice matters that put kids on a road to bigger problems — the so-called ‘school-to-prison pipeline.” In San Bernardino, cops, school officials, parents and community groups have started wrestling with how to balance demands for order — and security — without criminalizing kids.

There’s no state rule to define the role of school police, but some California districts have already taken steps to do that by imposing formal limits on police powers in school, and detailing what situations should require police involvement and what should be handled exclusively by educators.

This story is part of Criminalizing kids. Scrutinizing the use of law enforcement and courts to respond to kids’ conduct at school or other circumstances. . Click here to read more stories in this series.

Don’t miss another Juvenile Justice investigation: Sign up for the Center for Public Integrity’s Watchdog email.

The roots of a trend

The ranks of school cops have grown nationally since the 1999 massacre of students Juvenile injustice?: Kids in San Bernardino County pay the price with overzealous school cops - Salon.com: