The Invented History of 'The Factory Model of Education'

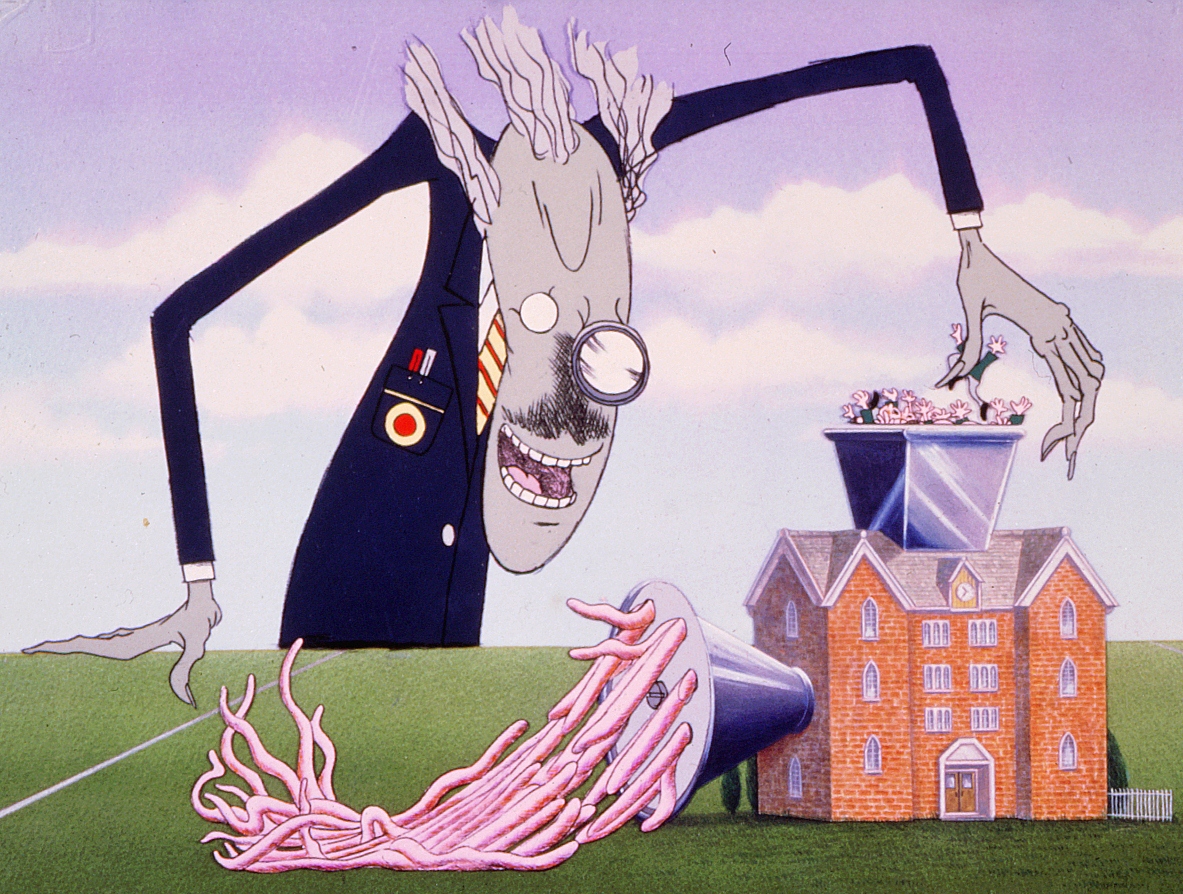

And so too we’ve invented a history of “the factory model of education” in order to justify an “upgrade” – to new software and hardware that will do much of the same thing schools have done for generations now, just (supposedly) more efficiently, with control moved out of the hands of labor (teachers) and into the hands of a new class of engineers, out of the realm of the government and into the realm of the market. Audrey Watters

“What do I mean when I talk about transformational productivity reforms that can also boost student outcomes? Our K–12 system largely still adheres to the century-old, industrial-age factory model of education. A century ago, maybe it made sense to adopt seat-time requirements for graduation and pay teachers based on their educational credentials and seniority. Educators were right to fear the large class sizes that prevailed in many schools. But the factory model of education is the wrong model for the 21st century.” – US Secretary of Education Arne Duncan (2010)

One of the most common ways to criticize our current system of education is to suggest that it’s based on a “factory model.” An alternative condemnation: “industrial era.” The implication is the same: schools are woefully outmoded.

As edX CEO Anant Agarwal puts it, “It is pathetic that the education system has not changed in hundreds of years.” The Clayton Christensen Institute’s Michael Horn and Meg Evan argue something similar: “a factory model for schools no longer works.” “How to Break Free of Our 19th-Century Factory-Model Education System,” advises Joel Rose, the co-founder of the New Classrooms Innovation Partners. Education Next’s Joanne Jacobs points us “Beyond the Factory Model.” “The single best idea for reforming K–12 education,” writes Forbescontributor Steve Denning, ending the “factory model of management.” “There’s Nothing Especially Educational About Factory-Style Management,” according to the American Enterprise Institute’s Rick Hess.

I’d like to add: there’s nothing especially historical about these diagnoses either.

Blame the Prussians

The “factory model of education” is invoked as shorthand for the flaws in today’s schools – flaws that can be addressed by new technologies or by new policies, depending on who’s telling the story. The “factory model” is also shorthand for the history of public education itself – the development of and change in the school system (or – purportedly – the lack thereof).

Here’s one version of events offered by Khan Academy’s Sal Khan along with Forbes’ writer Michael Noer – “the history of education”:

Khan’s story bears many of the markers of the invented history of the “factory model of education” – buckets, assembly lines, age-based cohorts, whole class instruction, standardization, Prussia, Horace Mann, and a system that has not changed in 120 years.

There are several errors and omissions in Khan’s history. (In his defense, it’s only eleven and a half minutes long.) There were laws on the books in Colonial America, for example, demanding children be educated (although not that schools be established). There was free public education in the US too prior to Horace Mann’s introduction of the “Prussian model” – the so-called “charity schools.” There were other, competing models for arranging classrooms and instruction as well, notably the “monitorial system” (more on that below). Textbook companies were already thriving before Horace Mann or the Committee of Ten came along to decide what should be part of the curriculum. One of the side-effects of the efforts of Mann and others to create a public education system, unmentioned by Khan, was the establishment of “normal schools” where teachers were trained. Another was the requirement that, in order to demonstrate accountability, schools maintain records on attendance, salaries, and other expenditures. Despite Khan’s assertions about the triumph of standardization, control of public schools in the US have, unlike in Prussia, remained largely decentralized – in the hands of states and local districts rather than the federal government.

The standardization of public education into a “factory model” – hell, the whole history of education itself – was nowhere as smooth or coherent as Khan’s simple timeline would suggest. There were vast differences between public education in Mann’s home state of Massachusetts and in the rest of the country – in the South before and after the Civil War no doubt, as in the expanding West. And there have always been objections from multiple quarters, particularly from religious groups, to the shape that schooling has taken.

Arguments over what public education should look like and what purpose public education should serve – God, country, community, the economy, the self – are not new. These battles have persisted – frequently with handwringing about education’s ongoing failures – and as such, they have shaped and yes changed, what happens in schools.

The Industrial Era School

Sal Khan is hardly the only one who tells a story of “the factory of model of education” that posits the United States adopted Prussia’s school system in order to create a compliant populace. It’s a story cited by homeschoolers and by libertarians. It’s a story told by John Taylor Gatto in his 2009 book Weapons of Mass Instruction. It’s a story echoed by The New York Times’ David Brooks. Here he is in 2012: “The American education model…was actually copied from the 18th-century Prussian model designed to create docile subjects and factory workers.”

For what it’s worth, Prussia was not highly industrialized when Frederick the Great formalized its education system in the late 1700s. (Very few places in the world were back then.) Training future factory workers, docile or not, was not really the point.

Nevertheless industrialization is often touted as both the model and the rationale for the public education system past and present. And by extension, it’s part of a narrative that now contends that schools are no longer equipped to address the needs of a post-industrial world.

Perhaps the best known and most influential example of this argument comes from Alvin Toffler who decried the “Industrial Era School” in his 1970 book Future Shock:

Mass education was the ingenious machine constructed by industrialism to produce the kind of adults it needed. The problem was inordinately complex. How to pre-adapt children for a new world – a world of repetitive indoor toil, smoke, noise, machines, crowded living conditions, collective discipline, a world in which time was to be regulated not by the cycle of sun and moon, but by the factory whistle and the clock.

The solution was an educational system that, in its very structure, simulated this new world. This system did not emerge instantly. Even today it retains throw-back elements from pre-industrial society. Yet the whole idea of assembling masses of students (raw material) to be processed by teachers (workers) in a centrally located school (factory) was a stroke of industrial genius. The whole administrative hierarchy of education, as it grew up, followed the model of industrial bureaucracy. The very organization of knowledge into permanent disciplines was grounded on industrial assumptions. Children marched from place to place and sat in assigned stations. Bells rang to announce changes of time.

The inner life of the school thus became an anticipatory mirror, a perfect introduction to industrial society. The most criticized features of education today – the regimentation, lack of individualization, the rigid systems of seating, grouping, grading and marking, the authoritarian role of the teacher – are precisely those that made mass public education so effective an instrument of adaptation for its place and time.

Despite these accounts offered by Toffler, Brooks, Khan, Gatto, and others, the history of schools doesn’t map so neatly onto the history of factories (and visa versa). As education historian Sherman Dorn has argued, “it makes no sense to talk about either ‘the industrial era’ or the development of public school systems as a single, coherent phase of national history.”

If you think industrialization is the shift of large portions of working people to wage-labor, or the division of labor (away from master-craft production), then the early nineteenth century is your era of early industrialization, associated closely with extensive urbanization (in both towns and large cities) and such high-expectations transportation projects as the Erie Canal or the Cumberland Road project (as well as other more mundane and local transportation improvements). That is the era of tremendous experimentation in the forms of schools, from legacy one-room village schools in the hinterlands to giant monitorial schools in cities to academies and normal schools and colleges and the earliest high schools in various places. It is the era of charity schools in cities and the earliest (and incomplete) state subsidies to education, a period when many states had subsidies to what we would call private or parochial schools. It is also the start of the common-school reform era, the era when both workers and common-school reformers began to talk about schooling as a right attached to citizenship, and the era when primary schooling in the North became coeducational almost everywhere. It was an era of mass-produced textbooks. It was an era when rote learning was highly valued in school, despite arguments against the same. And, yes, the first compulsory-school law was passed before the Civil War… but it was not enforced.

Maybe you think industrialization is the development of railroads, monopolies, national general strikes, metastasizing metropolises, and mechanized production. Then you mean the second half of the nineteenth century, and that is the era where the structural dreams of common-school reformers largely came to pass with tuition-freeThe Invented History of 'The Factory Model of Education':