De Blasio’s challenge: Paying for middle schoolers to stay late … and getting them to show up

When she heard last fall that she would have to stay in school until nearly 5 p.m., sixth grader Jenaba Sow tried to get out of it by telling her mom she had “after school-itis.” Although the new after-school program at P.S. 109 in Flatbush, Brooklyn, was presented as mandatory, Jenaba managed to skip the first three days.

But then the reviews starting coming in from her friends. There were snacks, one day even pizza. There were activities like science experiments and dance –– appealing to a girl who hates sitting still. Besides which, her mom’s work schedule at the nursing home had changed, and if not at school, Jenaba would have to bounce around between her uncle’s house and a babysitter’s.

Jenaba, like many of her peers, is now an after-school convert. After eight periods of academics, she finds herself looking forward to the hours between 2:30 and 4:50 p.m. “In after school, at least you’re doing something fun that you would enjoy,” said Jenaba, a slender, talkative girl who does well academically. She approves of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s idea to offer a city-run after-school program to every middle schooler in New York.

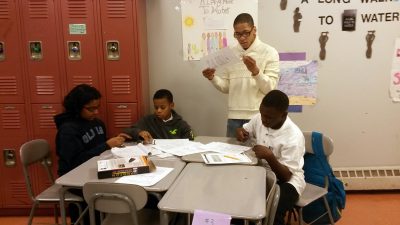

Students at Thurgood Marshall Academy work with one of their after-school helpers to figure out a science project. (Photo: Sarah Butrymowicz)

The plan, which would be voluntary, not mandatory, was a cornerstone of de Blasio’s educational platform during his campaign, and he’s trying to implement it by the 2014-2015 school year, funded along with universal pre-kindergarten by a tax on the city’s wealthiest residents. If successful, the initiative would be the largest after-school expansion in New York City’s history. It would solidify the city as a national leader in a movement to give young people more time to learn. And in theory, it would help close the gap between low-income students and their more affluent peers, since kids from wealthy homes are more likely to be participating in after-school activities already.

At a press conference this month, de Blasio said a high-quality after-school program can be a “game

At a press conference this month, de Blasio said a high-quality after-school program can be a “game

Great English teachers improve students’ math scores

Better English teachers not only boost a student’s reading and writing performance in the short-term, but they also raise their students math and English achievement in future years. That’s according to a working paper, “Learning that Lasts: Unpacking Variation in Teachers’ Effects on Students’ Long-Term Knowledge,” by a team of Stanford University and University of Virginia researchers presented

A mayor’s case to support the awkward years

New York City’s new mayor, Bill de Blasio, wants to offer after-school programs to all 200,000-plus middle school kids here. To that, you might ask, why middle school? Why not elementary or high? In an ideal world, of course, every child of every age would have a constructive way to spend the time between class dismissal and dinner, and money would be no object. But this is New York, where de Blas