Election 2016: What Teachers Can and Cannot Do

A little enforced New York City regulation requires that teachers remain politically neutral when performing official duties. In 2008, Mayor Michael Bloomberg ruled that public school teachers could not wear political buttons in the classroom. The teachers’ union challenged the ban but it was upheld by Federal District Court Judge Lewis Kaplan. Kaplan declared it was up to individual school districts to determine whether buttons in the classroom interfered with learning. However, he warned “school officials may not take a sledgehammer to freedom of expression.” A similar ban on political buttons in San Diego schools was upheld by California courts in 1996.

Courts have often given unclear guidelines in rulings on a teacher’s first amendment rights. However, what is clear is that school districts have flexibility in enforcing their policies - within limits. In 1972, a New York court sided with a teacher who was suspended for wearing an armband protesting against the Vietnam War. The court held that the teacher’s actions did not interfere with educational interests. In 2008, courts overturned an attempt by the University of Illinois to stop employees from attending political rallies and from displaying political campaign bumper stickers on campus.

In Pickering v. Board of Education (1968), the United States Supreme Court ruled that school employees have Constitutional protection when they are speaking about issues of a public nature. In that decision the court overturned a school district’s decision to fire a teacher for commenting on school expenditures in a letter to a local newspaper.

Last week a foreign language teacher in Smithtown, New York was “administratively reassigned” after she posted on her Facebook page, “This week is Spirit Week at Smithtown HS West. It’s easy to spot which students are racist by the Trump gear they’re sporting for USA Day.” While I do not believe her remarks are appropriate, the teacher did not express her views in her classes and is not accused of making remarks at school. As of this time there has been no formal disciplinary action by the school district and no court case.

Social media remains a minefield for teachers with no clear guidelines. An article by Michael Simpson, Assistant General Counsel for the National Education Association, documented a series of teacher firings for online posts.

In 2013 the New York City Department of Education (DOE) issued guidelines for “recommended practices for professional social media communication between DOE employees, as well as social media communication between DOE employees and DOE students.” Of course, the guidelines were not really recommendations. DOE supervisors were designated as responsible for monitoring and providing feedback on employee use of professional social media sites.

The guidelines also included “recommendations” for “Personal social media use” for “non work-related social media activity.” They include:

• DOE employees should not communicate with students who are currently enrolled in DOE schools on personal social media sites.

• DOE employees are encouraged to use appropriate privacy settings to control access to their personal social media sites.

• The posting or disclosure of personally identifiable student information or confidential information via personal social media sites, in violation of Chancellor’s Regulations, is prohibited.

• Personal social media use, including off-hours use, has the potential to result in disruption at school and/or the workplace, and can be in violation of DOE policies, Chancellor’s Regulations, and law.

The last recommendation is the one that concerns me and should concern the teachers’ union. Saying something has the potential to disrupt, even if it does not actually cause a disruption, is an open-ended assertion of authority over a teacher’s right to free expression.

To help teachers navigate treacherous waters, in 2015 the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) issued an updated version on the free speech rights of teachers developed by its Washington State branch.

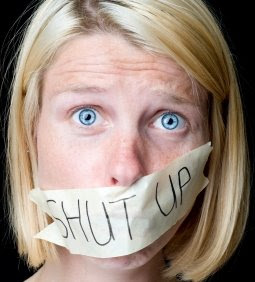

According to the ACLU’s interpretation of the Constitution and the law, “Generally, the First Amendment protects your speech if you are speaking as a private citizen on a matter of public concern. However, if you are speaking in an official capacity (within the duties of your job), your speech will not have the same protection. What you say or communicate inside the classroom is considered speech on behalf of the school district and therefore will not be entitled to much protection. Certain types of speech outside the school might also not be protected if the school can show that your speech created a substantial adverse impact on school functioning.” They warn if as a teacher “You post a ‘joke’ on Facebook about your students being lazy” it is not protected speech even though you are making it in your private capacity.

In addition, “School districts have the authority to control course content and teaching methods. You are generally considered to speak for the school district when you are in your classroom. Therefore, your speech in the classroom does not have much First Amendment protection. This can be a murky area, however. Some courts have ruled that schools cannot discipline teachers for sharing words or concepts that are controversial as long as the school has no legitimate interest in restricting that speech and the speech is related to the curriculum. In general, you should exercise caution so as not to give the appearance that you are advocating a particular religious or political view in the classroom.” The same goes for classroom displays.

While “The Supreme Court has ruled that students can wear armbands to school as an expression of their political views and that their right to free speech can only be limited if the speech would cause “substantial and material disruption” . . . The right Election 2016: What Teachers Can and Cannot Do | Huffington Post: