2 Reasons Why Bad Teachers Don’t Get Fired

Teaching is often viewed as a noble profession. Almost everyone in society has a strong connection to a teacher: Either their mom or other family member has been in the classroom for an entire career, their sixth-grade teacher changed the course of their life, or they realize the value of education in the workplace that follows. Many of the posts online about the nobility of teaching come from those in the profession themselves, who attest to the ways in which teaching has changed their lives for the better.

These are the reasons why talking about bad teachers, and how to replace them, becomes so difficult. It’s not easy to talk about a group of people who are disparaging the nobility built up around a profession, because too often it seems like an attack on the rest of the teachers, too. But teachers, and the unions that represent them, know there are a few among them who aren’t performing to par. Who, in fact, are doing the profession an injustice.

“No one wants bad teachers in classrooms,” said Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) in a discussion about education policies with the Aspen Institute. The AFT is the second largest teachers union in the country, and in this past year opposed a lawsuit that claimed the number of unsuitable teachers in California created an unequal learning environment for the state’s students. The AFT’s opposition wasn’t because the lawsuit sought to change tenure practices or fire the bad apples. Instead, Weingarten said she and the union opposed the court proceedings because the legal action pitted students against teachers.

The heart of the issue for firing bad teachers most recently was the focus of a court case in California, brought by nine students within the state and backed by Students Matter, a coalition of Silicon Valley businessmen led by entrepreneur David Welch. Though some of the articles to follow, including Time’s coverage in its November issue, garnered fierce criticism by the teaching community, it did point out that it was the first case to link the quality of a teacher with a student’s right to an education.

According to the decision in Vergara v. California, Judge Rolf M. Treu found that the effect of “grossly ineffective” teachers have adverse affects on the education students receive. “The evidence is compelling,” Treu wrote in his decision. “Indeed, it shocks the conscience.” Treu cites findings from experts who testified in the case: One ineffective teacher costs students $1.4 million in lifetime earnings within a single year. Based on a four-year study, students in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) who were taught by a teacher in the bottom 5% of competence lost 9.54 months of learning in a single year, compared to students with average teachers.

Teacher tenure

One of the main contentions within the court case, and the larger discussion of firing underperforming teachers, is that tenure often protects the people who are making egregious errors in the classroom. LAUSD Superintendent John Deasy testified in the case on behalf of the students, saying that the tenure laws in California as they stood were “patently problematic.”

In practice, lifelong tenure in the state is determined in 14-16 months of a teacher beginning his or her career in any public school, Deasy called this a “ridiculous” short amount of time that doesn’t accurately reflect the teacher’s abilities or means of evaluating whether they are deserving of such status. Plus, the overwhelming majority of teachers receive tenure without incident. In the L.A. district for example, the rate of teachers denied tenure in years past has been as low as 2%. Deasy and Weingarten discuss the court case in depth in the video posted above.

Deasy quickly clarified that tenure should be given to teachers who have proven themselves worthy, but that one year and two months, along with likely three evaluations by a principal, isn’t enough to determine that. However, Deasy said he is confident more time wouldn’t harm the teachers who are actually going to succeed in the profession. “No system in the world would willingly design itself to get rid of great talent,” he said.

But on the flip side, Weingarten said good teachers would say that tenure ensures they are able to take risks in the classroom, to be unconventional in order to encourage learning, even when administrators or parents aren’t sure it’s the right move. In the discussion at the Aspen Institute, Weingarten gave an example of a teacher in Indiana who was dismissed because an administrator wanted to hire a friend. She also used an example from her own teaching career, in which an administrator gave her an “unsatisfactory” rating for holding a mock court case in her classroom. Had the decision not been reversed later, Weingarten said, she could have been fired in the state of New York as an untenured teacher.

The legal costs

The process for firing a teacher might begin in a school district, with discussions among school board members and union representatives. But the outcome is often decided for good in the courts system, a process that takes too long and costs enormous amounts of money. Even Weingarten, in the Aspen discussion, acknowledged that all sides should be working to make sure it doesn’t take 10 years (or even one) to fire a teacher guilty of gross misconduct or incompetency.

In California alone, the Vergara case experts estimate that 1-3% of the state’s 275,000 teachers are “grossly ineffective.” For those of you without calculators for brains, that’s roughly between 2,750 and 8,250 teachers who aren’t up to snuff. But the unions will go to bat — or court — for their members, especially when there’s any question of subjectivity. In many cases, that can lead to costs of hundreds of thousands of dollars for the school districts, amounts that are increasingly difficult to swallow in the face of what many people would say is a lack of adequate funding for public districts. In one particular case, the L.A district settled with a teacher after a five-year court battle, agreeing to pay $150,000 in lawyer fees on top of the teacher’s $300,000 in paychecks earned during that time.

Your Reaction?

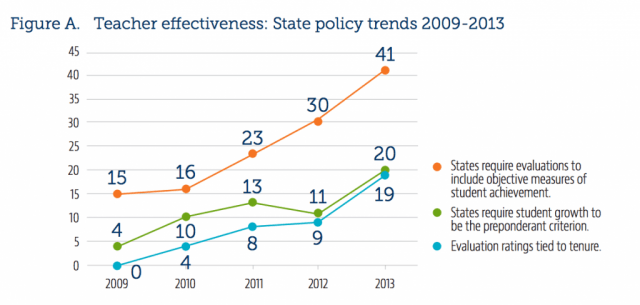

Source: National Council on Teacher Quality

Are there changes ahead?

Progress by any means to solve this issue will likely be slow. For one, the issue of teacher effectiveness should never be viewed in a bubble, which the AFT believes is the case in the Vergara decision. “”It’s surprising that the court, which used its bully pulpit when it came to criticizing teacher protections, did not spend one second discussing funding inequities, school segregation, high poverty or any other out-of-school or in-school factors that are proven to affect student achievement and our children,” an AFT response to the court decision reads. The union, as well as the state of California, is appealing Treu’s ruling.

But another reason progress will likely be slow is that education is largely left to state authority. States such as Indiana and Louisiana have already tied student performance to some aspects of teacher evaluations. Those, in turn, are tied to whether a teacher in those states receive tenure. Evaluations are also tied to student performance in numerous other states, a trend that continues to grow. A report from an advocacy group,