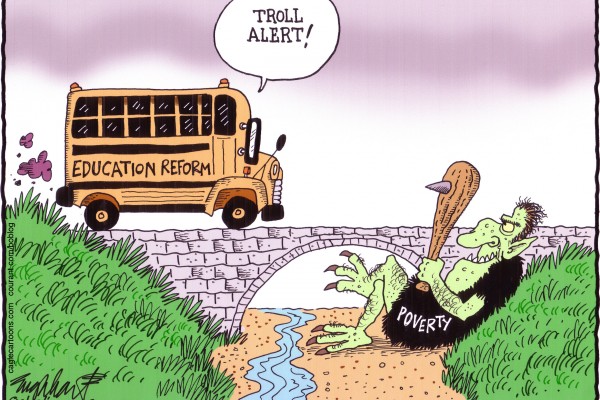

URBAN SCHOOL SOLUTIONS WON’T BE EASY – OR CHEAP

26 FEB 2015

26 FEB 2015  POSTED BY AHAMILTON

POSTED BY AHAMILTONBY JOHN THOMPSON

I strongly support the work of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies to close the racial “discipline gap.” I want to be clear in my agreement with “Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?” by Daniel Losen, et al.

Although I intensively studied nearly 15 years of Oklahoma City suspension data, and taught at the state’s lowest performing high school, I am surprised that in the two years after I left the classroom that the Oklahoma City Public Schools became “one of the top ten highest-suspending districts at the secondary level for all students, and is the highest suspending district in the nation for black secondary students.” Moreover, between 2010 and 2012, “overall suspension rates at the high school level also increased from 24.7% to 45.2% during the same period.”

The latest database shows that at the secondary school level, OKCPS “suspension rates for black students climbed dramatically from 36.3% to 64.2%.” [I have my own theories on why, at a time when education funding was dramatically cut, the rate ballooned, but I will limit myself to what I witnessed and studied.]

I support the efforts of Losen and the Center for Civil Rights Remedies. Students can’t learn if they are not in class and we need to invest in Restorative Justice, and other alternatives to suspensions. Neither do I claim that educators are blameless or that we don’t need to invest heavily in professional development. I just worry that systems will, once again, take the cheap and easy approach of claiming that better classroom instruction is enough to reduce suspensions.

For that reason, I will recount some of my experiences. I am not offering excuses for schools or blaming the problem solely on the history of out-of-school oppression. I’m merely placing today’s problems in a context.

Reformers tend to blame teachers’ “Low Expectations” for chronic disorder. But I was punched twice before clocking in for my first day in a neighborhood school. The assailants in the two-on-one gang-related fight I broke up were sent off, without consequences, by an overburdened assistant principal.

When I entered the classroom as a 39-year-old rookie, I already had nearly a decade of wonderful experiences nurturing poor children of color. Some of my first freshmen students and I had spent the summer in a camp for low-income kids. As always, the rural white people who ran the camp spoke effusively about the self-control and wonderful manners of the campers, who often were out of control in school. When I saw the deplorable behavior of so many of my young friends as they walked into the school, I realized that a situation this surprising and acute must be the legacy of a decades-long history. Teens, who were so responsible on the job or in church, would not be behaving this way unless it was the result of a complex and engrained set of dynamics.

In a system that only invested $1,875 per student, the job of principals was to “just keep the plate spinning until June.” It was understood that violence could only be shunted off to the edges of the school property. A decade later, No Child Left Behind [NCLB] helped increase funding, but the new resources were directed towards tested subjects, meaning that students and teachers didn’t see a meaningful increase in spending that would have made a real difference.

Much of our problem is that when teachers call for “discipline,” non-educators hear a request for punishment. Teachers tend to be so frustrated with the lack of disciplinary consequences that our complaints sound like demands for “law and order.” We cannot punish our way to safe and orderly schools. But neither can we continue to turn a blind eye to behavior that undermines instruction and teaches children the worst possible lessons about functioning in the adult world.

I was often told that students behaved well for me because I had earned their respect. Since those observations were meant as a compliment, my response took administrators aback. “That’s the problem,” I would say, teachers shouldn’t have to go to such extraordinary lengths to prove themselves to their students.

The Center for Civil Rights Remedies reports on the disparate suspensions of Oklahoma City Urban School Solutions Won’t Be Easy – Or Cheap | Oklahoma Observer: