‘Janus’ and Its Supreme Court Enablers

The stacking of the U.S. Supreme Court with anti-union justices has allowed the right-to-work movement to circumvent, and undercut, pro-union state policies.

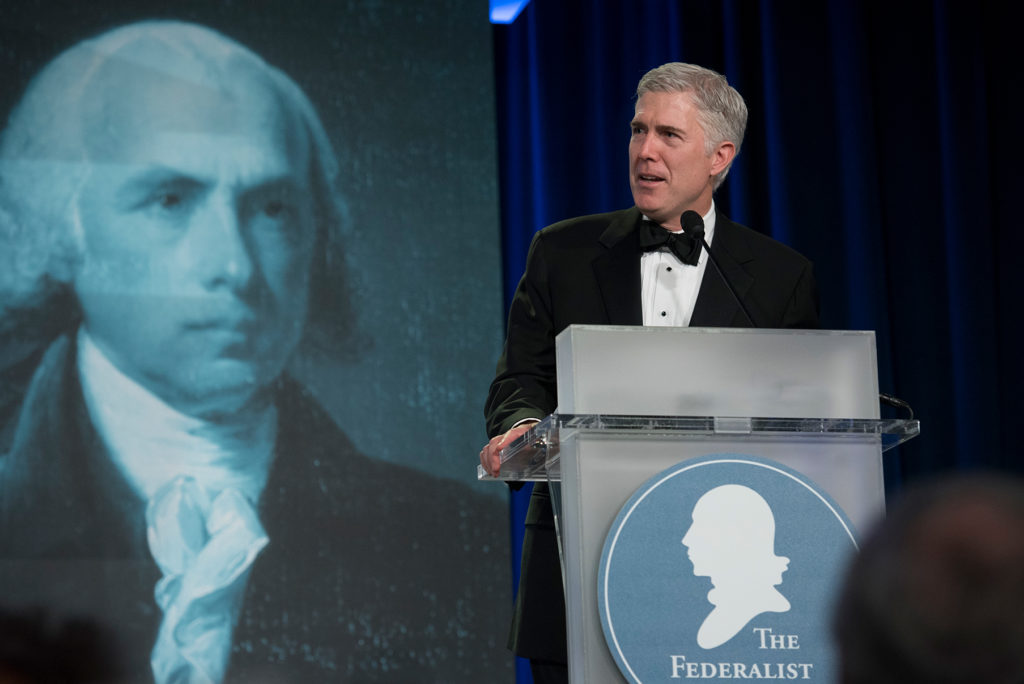

n the fall of 2015, the Federalist Society, a conservative legal organization with a libertarian bent, held its annual lawyers convention at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC. The three-day event included a panel that reviewed the past decade of the John Roberts court, and featured Michael Carvin, a high-powered attorney with Jones Day, who in recent years has taken the fight against labor unions to the Supreme Court.

Carvin began his remarks, curiously, by downplaying the chief justice. “The real consequential thing that happened 10 years ago, frankly, was not John Roberts replacing Chief Justice Rehnquist,” he told the crowd. Instead, he argued, the dramatic shift had been the replacement of Sandra Day O’Connor by Samuel Alito.

There was a lot that Carvin and Alito had in common. Both were members of the Federalist Society—Alito had joined in 1983, a year after it was founded; Carvin has served as the chairman of the Society’s Civil Rights Practice Group. The men also had worked together at the Justice Department during the Reagan administration. In 2006, when George W. Bush nominated Alito to the Supreme Court, it was Carvin who repeatedly stood up for his former colleague’s far-right views. Carvin even went so far as to defend him when the Wall Street Journal revealed that Alito, when applying for the Reagan position, had written that he disagreed with the Supreme Court decision that had established the “one person, one vote” doctrine as the framework for American elections.

At the Mayflower Hotel, Carvin argued that Alito represented “some baby steps toward the return of law.” Just two months later, Carvin was in front of Alito and the eight other justices, arguing a case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, that sought to strip public sector unions from “fair share” fees they collected to represent workers who declined to join the union. (By law, a union must represent all workers in a bargaining unit, whether or not they choose to join. It was a far-reaching case that could cripple the power of unions, and would represent the crowning achievement of a conservative movement that had been decades in the making. Disclosure: The California Teachers Association is a financial supporter of this website.)

In a unanimous 2009 decision, the court reaffirmed a 1977 case, Abood v. the Detroit Board of Education, which had ruled that unions could charge such fees. But the ascent of Alito had helped shift the court in a vehemently anti-union direction, and it was widely expected to rule against the unions in Friedrichs. Then Antonin Scalia suddenly died, and the court deadlocked, four-to-four. The reprieve was only Continue reading: 'Janus' and Its Supreme Court Enablers | Capital & Main