Race Is Always the Issue

Blackness has been relentlessly disparaged in American discourse—both covertly and overtly.

Every conversation about resources in the United States is also about race and racism. Like parents choosing a neighborhood for its “good schools,” Americans talk about prison and crime as a means of discussing race and racism in polite company.

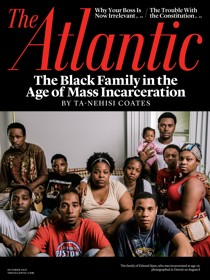

One needn’t hate Hispanics to choose a school system with no Hispanics. One need not say that black people are violent apes to call the police when an injured human being who happens to be black knocks on your door for help. Freedom—from being stopped and frisked; from predatory criminal justice fines; from cells—is arguably the resource from which every other resource flows: education, marriage, income, wealth, happiness, actualization. In “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a decoder ring for the language of criminality, revealing that it rests on the idea that America can only be great so long as America is fundamentally white.

During my doctoral training, Moynihan was offered as a cautionary tale to young academics. Moynihan, they said, dared to tell the truth about the culture of poverty in black communities. As a result, the liberal elite and angry black-activist oligarchy ran him out of society’s good graces, if not exactly out of town. We were warned against dabbling in social prescriptions: “Look what they did to Moynihan!”

That he made it despite being “made into a racist,” as he put it, refutes the idea that being labeled a racist is some scarlet letter. It also raises questions about the renewed interest in revitalizing Moynihan’s reputation. Orlando Patterson and Ethan Fosse wrote in a new book that “history has been kind to Moynihan.” I agree. History has been kind to Moynihan. But it is not that empirical evidence of a deep culture of poverty among blacks has proven Moynihan’s case. Instead, the rapid acceleration and ruthless efficiencies of incarceration have made Moynihan’s theses seem prescient by intensifying every structural condition of race, poverty, and criminality in the United States. Moynihan is prescient only if one ignores that Moynihan went on to participate in the kind of policies and ideology that perpetuated the conditions he was originally critiquing. That kind of prescience is called winning by owning the rules of the game.

As fortune (or power) would have it, the narrative of a crime wave is reemerging. In the wake of Black Lives Matter protests all across the country, standing against The Proxy Wars That Constrain African Americans - The Atlantic: