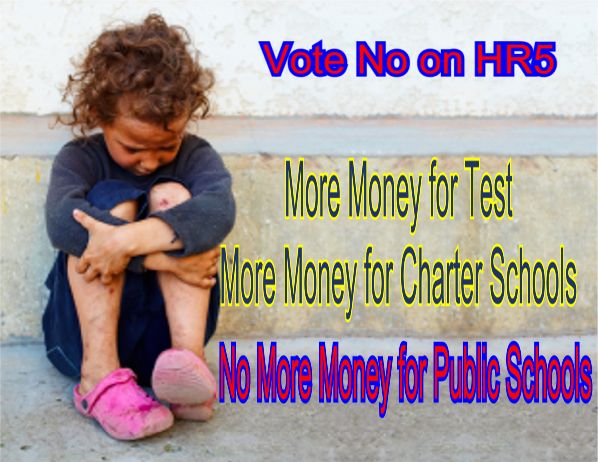

No ESEA Bill Is Better Than One That Fails to Protect the Poorest Children

#NOonHR5

#STOPHR5 #NOonHR5 US Representatives on Twitter Find your Member Hit them with a Vote No on HR5 Tweet http://bit.ly/17s6O1b

For fifty years Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA)has been the primary source of federal funding targeted to schools to serve poor children. Its purpose has been to raise achievement for poor children through extra support to their schools to help meet their greater educational needs. Sadly, from the beginning states didn’t keep their end of the bargain.

In 1969, the Washington Research Project (the Children’s Defense Fund’s parent organization) and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. partnered with others and examined federal audit reports on how Title I funds were being used and talked to numerous federal, state, and local officials and community leaders and parents about how those critical funds were being spent. Our report, Title I: Is It Helping Poor Children?, found the answer to our question was a resounding “No.” Rather than serving the special needs of poor and disadvantaged children, many of the millions of dollars Congress appropriated had been wasted, diverted, or otherwise misused by state and local education agencies. Title I funding was often being used as general aid and to supplant -- rather than supplement -- state and local education funds, including for construction and equipment unrelated to Title I goals. For example, Fayette County, Tennessee used 90 percent of its Title I funds for construction of a predominantly Black school despite a recent federal court order that the school system desegregate, and Memphis, Tennessee used Title I funds to purchase 18 portable swimming pools in the summer of 1966.

The Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) subsequently conducted several other major studies that reinforced the importance of federal accountability for money targeted to help children most in need, especially poor children and children of color. In CDF’s first report, Children Out of School in America (1974), after knocking on thousands of doors in census tracts across the nation and interviewing many state and local school officials, we found that if a child was not White, or was White but not middle class, did not speak English, was poor, needed special help with seeing, hearing, walking, reading, learning, adjusting, or growing up, was pregnant at age 15, was not smart enough, or was too smart, then in too many places school officials decided school was not the place for that child.

We should learn from and correct our mistakes and stop repeating them over and over again for our children’s sake. It is crucial that a strong Title I program reach the children in areas of concentrated poverty if and when ESEA is reauthorized. Unfortunately the House Education and Workforce Committee, charged to lead in moving an ESEA reauthorization bill in the House of Representatives, just approved abill (H.R. 5) in a party line vote that fails to target the needs of the poorest children by adding a “portability” provision assuring these children less help. AASA, The School Superintendents Association, and many others join us in opposing the portability provision.

The portability provision in H.R. 5 would move us backwards by distributing the same amount for a poor child regardless of the wealth of the district or school she attends. This will unravel the intent of Title I by taking resources away from children in areas of concentrated poverty and offering extra resources to schools and districts with a few poor children who may not need them. The poorest students in schools with the No ESEA Bill Is Better Than One That Fails to Protect the Poorest Children | Marian Wright Edelman: