Children in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to see their local schools close.

Shrinking public finances have meant many cities and municipalities have looked to cut costs, with education not being spared. In new research, Jin Lee and Christopher Lubienski examine the effects of Chicago’s school closures, which have been justified by falling enrollment numbers. They write that schools in poorer areas are often likely to be the first targets for closure, a trend which means that there are fewer schools available for children – often African American and Latino – in less advantaged neighborhoods.

Public schools in the US are increasingly being shut down when they have been identified as underperforming on the basis of test scores and graduation rates. The traditional approach to school closure has been to reduce financial losses caused by empty classrooms and under-enrolled schools, especially in rural school districts. Indeed, this classic approach to maximizing efficiency is now evident in school closure policies in larger cities which are experiencing out-migration and depopulation. But now it has been combined with the idea of punishing apparent organizational underperformance.

The Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the third largest school district in the United States, is no exception. Chicago announced in the spring of 2013 that 54 primary schools would close in the upcoming school year, and that economies of scale provided justification for determining which schools to be closed. Considering that the number of primary school-age children has decreased by 24 percent in Chicago over the last decade, it is not surprising that school closures were accelerated in particular areas experiencing this decline. However, it is important to think carefully about where schools are closed and how that may impact students in terms of spatial equality.

In new research, we examine the possibility that school closings shape inequitable access to schools particularly for children in less advantaged neighborhoods. By taking into account travel time to schools, our study finds the CPS school closing policy—based on the capacity and the number of empty seats at schools—raises the likelihood that students in segregated communities have less access to neighboring schools.

Beware of location!

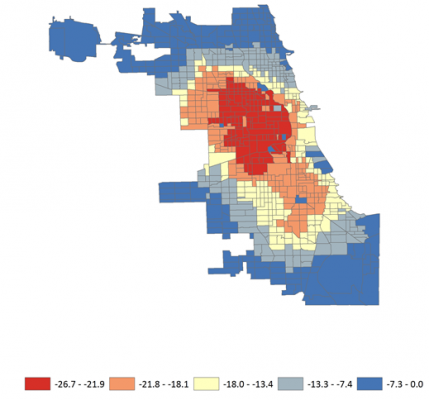

CPS has closed schools before. Chicago can close a school if the student enrollment is less than 80 percent of ideal enrollment. Thirteen primary schools were indeed closed for underutilization between 2001 and 2006, despite continuing debates over harms and benefits of school closings in large urban school districts. Yet, the reason that the latest school closing move in the fall of 2013 attracted such unwelcome attention is because of the scale: Chicago closed and relocated about 8 percent of schools. As shown in Figure 1, a substantial decrease in access to neighboring schools after these mass school closures occured in the north of downtown Chicago.

Figure 1 – Access change after the school closures

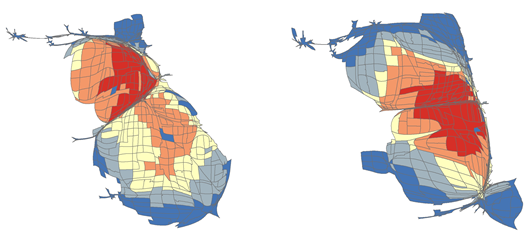

More precisely, the policy produced a notable change in access in areas with a high density of both African American and Latino American children. This suggests that school closures may be depriving students in particular areas of the opportunity to attend more convenient neighboring schools. As shown in Figure 2, the areas with a relatively large population of minority children are gradated in orange and red colors. This tells us that children in these areas experience significant declines in access after school closures.

Figure 2 – Access change by African American (left) and Hispanic (right) children

In Chicago, when neighborhood schools close, one of the the biggest potential problems is that childrenChildren in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to see their local schools close. | USAPP: