Control Issues in Charter Schools

An Examination of New York State Comptroller’s Audits

In Brief

Charter schools are a controversial topic in education and politics because the public funding they receive makes them quasi-public organizations; thus, political groups, authorizing bodies, and local communities are all greatly interested in their financial results. Even CPAs who specialize in school district audits may need a refresher on charter schools, which have very different governance concerns and audit risks. This article provides an overview of New York State charter schools, including funding, governance structure, and audit requirements—and how these characteristics create unique financial audit issues for CPAs. The authors’ examination of 54 internal control audits of New York charter schools conducted by the Office of the State Comptroller over the past six years can help CPAs become familiar with some common charter school control deficiencies.

* * *

Charter schools are privately managed public schools, independently operated under an authorizing body; in New York State, this is the Board of Regents (sometimes through an approved application forwarded by a chartering entity, such as the State University of New York Board of Trustees). The type of authorizer and level of oversight varies from state to state, but in New York State, charters are required to file an annual report that includes detailed enrollment and fiscal information. The New York State legislature decided in 2010 that charters would be subject to the same ethics and conflict of interest laws that pertain to school districts, which empowered the New York State and New York City comptrollers to audit charter school operations. The New York State charter board reassesses schools every five years and, at that time, can deny continuation of a charter.

Management of charter schools varies: though every New York State charter school must be a nonprofit organization under Internal Revenue Code section 501(c)(3), they may operate independently or under either a nonprofit or for-profit management company or sponsoring organization. Though a small number of schools operate under for-profit management, starting in 2010 this practice was not allowed for new charters. Regardless of the charter’s organization, school board members are forbidden from having a financial interest in the management company or any other vendor of the school. Any conflicts of interest should be disclosed in the annual report filed with the New York State Department of Education.

Charter schools are funded in accordance with state law, based on per-pupil spending in the students’ home school district. They may receive donations as a charity, but are not allowed to charge tuition or impose special entrance requirements; they can issue bonds, but may not pledge per-pupil funding to repay the debt. Charters generally have increased autonomy with respect to budgeting and governance because they are independent of local school boards.

Required Audits

New York State charter schools are required under the terms of their charters to have at least one annual financial statement audit, conducted in accordance with U.S. GAAS and U.S. Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS) and comparable in scope to school district audits (although, as nonprofits, charter schools follow FASB rather than GASB standards). In addition, an initial statement on internal controls is required for new schools within 120 days of issuance of a charter; any deficiencies must be remedied promptly. Schools might also be subject to particular agreed-upon procedures if they receive certain grant funding from the state. Federal funding of $750,000 or more will subject a charter school to the Single Audit Act, which requires an independent audit with specific guidelines issued by the Office of Management and Budget.

Audit Guidance for CPAs

In 2016, New York State charter school audits took on added importance as additional funding was allocated to charters and the cap on the number of schools was raised to 460. Following these changes, the New York State Department of Education noted variations in the audit quality and in auditors’ understanding of charters; it also published an audit guide for charter schools (“Charter School Audit Guide,” http://bit.ly/2Jfm4T5). The guide addresses some issues unique to charter schools:

- A legal requirement to maintain an escrow account with monies to cover legal and audit expenses related to potential dissolution

- The need to confirm receivables from school districts billed for tuition and other parties, such as USDA food service

- Payroll for teachers at nonprofit charters who are on 10- or 11-month employment contracts

- FASB accounting standards for pensions applied to state retirements

- Investment policies

- Per-pupil funding

- Co-locations of charters in public school buildings that would otherwise be empty

- Management fees

- Other fraud considerations, such as misappropriation of assets due to the high use of credit cards and related-party transactions.

The guide also outlines issues specific to financial statement presentation in charters and the separate report on internal controls required under GAGAS. In addition, it includes Single Audit Act guidance for schools receiving significant federal funding, as well as the agreed-upon procedures guidance required for recipients of certain New York State grants. Finally, the guide contains many useful audit schedules and templates for CPAs conducting audits of New York State charters.

Control Issues at Charter Schools

The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools estimates that there were 6,939 charter schools educating 3.1 million students in the United States during the 2016/17 school year (http://bit.ly/2H4S4bR). Thus, strong financial controls and CPA audit expertise are crucial for prudent management of this growing education sector.

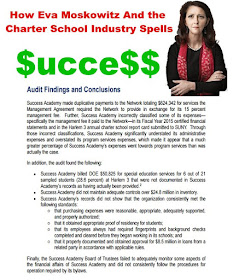

The Center for Popular Democracy is one proponent of increased accountability for charter schools. In its 2014 report, “Charter School Vulnerabilities to Waste, Fraud and Abuse” (http://bit.ly/2GyA0Jz), examining large charter markets across 15 states, it found evidence of control failures, including—

- public funds being used for personal gain,

- school revenues being used to support charter operators’ other businesses,

- illegal inflation of enrollment numbers, and

- revenue generated from services not provided.

The economic magnitude, rapid growth, and relatively new and variable regulatory environment constitute significant fraud risk, which merits a closer look at the audit practices and control pitfalls in charter schools.

Many charter schools in New York State are located in New York City, where audit responsibility rests with the city comptroller; however, a search of the city comptroller’s website revealed only four audits of charter schools. As a result, this discussion examines audits of charter schools outside the city, which are subject to audit by the Office of the State Comptroller (OSC). The OSC conducted audits of internal controls in 54 charter schools between 2011 and mid-2017.

Many of the control issues uncovered by the OSC are related to internal control issues common in both traditional school districts and charter schools, such as procurement, payment, and payroll or a need for information technology policies (“Routine Public School Audit Issues” in the Exhibit). Other internal control problems might be less familiar to auditors because they deal with matters that would not arise in a regular school district (“Charter-Specific Issues” in the Exhibit). This examination of the state comptroller’s audits yielded 205 audit recommendations (see the Exhibit).

Exhibit

Public School Issues versus Charter School Issues

The economic magnitude, rapid growth, and relatively new and variable regulatory environment constitute significant fraud risk.

Of the 54 audits, 38 addressed charter school–specific control issues related to the following four areas: contracts with sponsoring organizations, conflicts of interest, space issues, and residency and billing issues.

Contracts with Sponsoring Organizations

Charter schools typically have a sponsoring organization (i.e., a foundation or a management company) that Continue reading: Control Issues in Charter Schools - The CPA Journal: