School reform will not be a priority for the new president

The era of regulation-driven reform is coming to an end

FOR a president, making education policy can be like running a school with thousands of unruly pupils. He can goad states and coax school districts, offering gold stars to those who shape up. But if a class is defiant he can do little. Just 12.7% of the $600bn spent on public education annually is spent by the federal government. The rest is split almost equally between states and the 13,500 districts. Many presidents end up like forlorn head teachers: America spends more per child than any big rich country but its pupils perform below their peers on international tests.

Despite the constraints, George W. Bush and Barack Obama both used the regulatory power of the federal government to spur reform. Through the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, the Republican president launched a flurry of standardised tests, sanctioning schools whose pupils failed to progress. Through his “Race to the Top” initiative, announced in 2009, the Democratic one offered cash to states in exchange for reforms such as higher standards and evaluating teachers based on pupils’ results. Similar policies were implemented by 43 states in exchange for federal waivers from the testing mandates of NCLB. Mr Obama has also championed charter schools, the part-publicly funded and independently run schools hated by teachers’ unions.

But the era of regulation-driven school reform is now coming to an end, for two reasons. The first is the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), passed in December as a replacement for NCLB. ESSA hands back power to states over standards and tests, making it hard for a future president seeking to micromanage school reform.

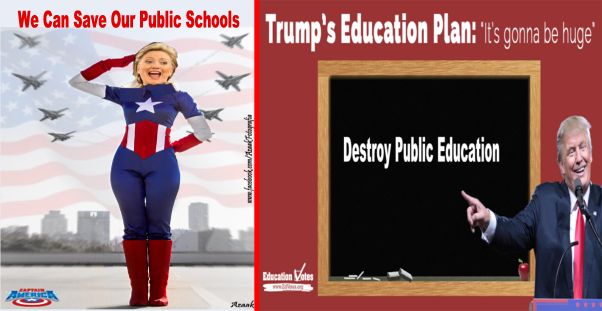

In any case, neither Donald Trump nor Hillary Clinton are inclined to imitate the past two presidents. Mr Trump is “totally against” and “may cut” the Department of Education. Declaring that “it is time to have school choice”, in September he pledged to give states $20bn to fund school vouchers for parents of poor children. Mrs Clinton has also been keen to defer to states. This is partly because she knows ESSA shrinks her room for manoeuvre. But she has also made a political calculation. Unlike Mr Obama, she is backed by teachers’ unions. They oppose tying teacher evaluations to pupils’ results and want to keep the caps on charter schools in place in the 23 out of 43 states that permit these schools. (On November 8th Massachusetts will vote on whether to raise its cap. Polls are finely poised.)

Mrs Clinton has been studiously ambiguous on such limits, to the regret of reformist Democrats, who note that in most cities charter schools outperform ordinary public schools. Though she has sent Tim Kaine, her vice-presidential nominee, to mollify funders of charters, they are braced for a change of tone. Charters will still expand. But they will receive less federal support. “We reformers have had a big tailwind under Obama, which School reform will not be a priority for the new president | The Economist: