When It Comes to School Choices, It's a Privilege to Have Fewer

While a range of options might seem like a plus, there are costs.

It’s no secret that public school funding comes largely from local property taxes —a model that has produced, in the words of the social-justice writer Jonathan Kozol, savage inequalities. Schools in lower-income neighborhoods often wind up with fewer dollars per student than those in wealthier areas, even though students from low-income families are often the ones most in need of extra support.

But are kids who live in poor areas confined to local schools? New research suggests that at least in Chicago, which contains the nation’s fourth largest school district, they’re not. Policies that decouple where kids live from where they must attend school—crafted with the best of intentions—have given poor students lots of “choices” when it comes to where they learn. But that’s not necessarily a good thing.

Julia Burdick-Will, an assistant professor of sociology at Johns Hopkins University, obtained and analyzed individual-level data for more than 24,000 eighth-graders enrolled in Chicago Public Schools in the fall of 2008. The data included the students’ census block group and tract, their standardized test scores, and the high schools they entered the fall of 2009, which numbered 122.

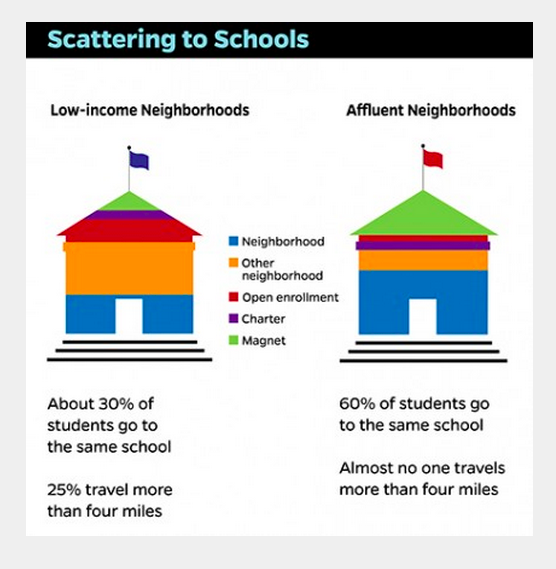

She found that, compared to kids from wealthier neighborhoods, students from the poorest areas actually attended a wider range of schools in terms of quality (based on University of Chicago’s metric, which includes average test scores, graduation rates, and safety), type (default neighborhood schools, schools in other neighborhoods with open enrollment policies, charter schools, and magnet schools, to name some), and sheer number.

While a range of school options might seem like a plus, there are costs. Though most students who chose to leave their neighborhood school went to higher-quality institutions, 15 percent traveled to a school that was objectively worse than their local option. And most were traveling further to school, spending more time commuting.

By contrast, students who lived in higher-income neighborhoods tended to stay at their default local schools, which were usually of higher quality than those in low-income neighborhoods. But when wealthier kids did choose, they generally went somewhere even better—a selective-enrollment school, for example, or a magnet school, where slots are competitive.

Why do poor families wind up sending kids away from local schools, when the outcome isn’t guaranteed to be better? The perceived quality, as well as the safety, of schools in low-income neighborhood might be two factors. “More violent neighborhoods in Chicago tended to have more scattering,” Burdick-Will says. “Some parents might be thinking ‘anywhere is better than here.’”

Burdick-Will’s research, which she presented at the American Sociological Association annual meeting in August, was less about why low-income students scatter across city schools, and more about proving that they do. She says that academics often assume poor children are “trapped” in local, underperforming schools, with the exception of special bussing programs. “This isn’t about a specific policy that buses a few hundred kids,” she says. “This is happening all the time, and only in certain neighborhoods.”

Burdick-Will’s research has limitations. She studied only one cohort of eighth-graders in only one year. And this was only within Chicago Public Schools. It would be wrong to conclude that this is the reality on the ground everywhere.

Still, many districts nationwide have policies that break the link between home and school location. In a 2007 national survey, 50 percent of parents reported that at least some choice was available within their children’s school districts.

Burdick-Will’s research also hints at one little-seen explanation for why schools in low-income schools underperform. She found that higher-achieving students were more likely to choose a school away from their default neighborhood schools, leaving those institutions with higher concentrations of struggling kids.

Those disproportionate numbers of lower-achieving students put more strain on resources, which are already scarce in low-income schools. That can lead to further depopulation, and even shuttering. Jelani Cobb’s latest in the New Yorker details how the decline and recent closure of Queens’ Jamaica High In Chicago, Students From Low-Income Neighborhoods Commute to Local School More Than Wealthier Peers - CityLab: