Forty Years Later

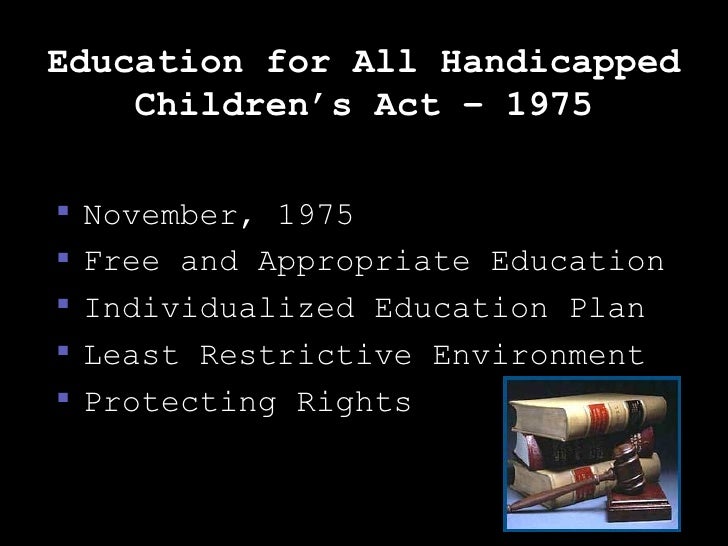

Public Law 94-142, “The Education of All Handicapped Children Act of 1975,” passed not long after I began reporting on education, and it became the first issue that I dug into deeply on my weekly NPR series. A lot has happened since then, much of it very positive, which makes the 40th Anniversary an occasion to celebrate–while continuing to search for ways to improve the learning opportunities for kids with special needs.

The term “Handicapped” was soon cast aside, and “Special Needs” became the term of choice. Before long “Handicapped” became the field’s “H word,” never to be spoken in public. Word games ensued. Some preferred “Exceptional” as the descriptive adjective–and in fact it had been the Council for Exceptional Children in Washington that pushed hardest for passage of legislation in the 1970’s. Militants often referred to non-disabledchildren (and adults) as “temporarily able-bodied,” but that did not catch on.

Although the vote in the House and Senate had made it veto-proof, PL 94-142 was not universally popular. In a break with tradition, President Gerald Ford refused to allow photographers into the room when he signed the bill. He was upset and angry about the precedent the law was setting–requiring services but not providing the money. Somewhere in our video archive is an interview with then former President Ford, in which he reflects on the ‘unfunded mandate’ of PL 94-142, which required schools to serve these students but did not come close to providing the funds. He predicted–correctly–that this would become an albatross around the necks of school boards.

PL 94-142 required that every child who was diagnosed and labeled be provided with an IEP, an “Individualized Education Plan,” that would serve as a road map for their education. That essential provision also created a bureaucratic situation, sometimes a nightmare, for parents and administrators.

The new law also created, almost overnight, a new area of specialization for teachers and a growth industry for schools of education. Even today, it’s the easiest area of education to find a job.

The law and its successors have created other problems, most notably the “lawyering up” of parents determined to force public schools to pay for expensive private school education for their children with special needs. It’s not a ‘cottage industry’ for lawyers, the special education attorney Miriam Freedman notes, but a “mansion industry.”

The new law required that students with disabilities be educated in the “least restrictive environment,” a reaction Forty Years Later | Taking Note: