Connecticut Makes Rare Progress On School Segregation As America Moves Backwards

When Connecticut high school senior Akbar Maliki looks back on his high school experience, he can think of only one negative: his school has made him so open to and accepting of diversity, he says, that he worries about his ability to make friends with people from too-similar backgrounds.

"I'm always going to be looking for the next diverse group. It's hard for me to be surrounded by the same types of people," Maliki, who moved to the United States from Indonesia as a child, told The Huffington Post.

Unlike so many around the country, Maliki's school is deliberately diverse. Its student body is slightly over half black, about a quarter white, 16 percent Hispanic. Nearly half of its students are eligible for free or reduced price lunch. When Maliki looks around his lunchroom, he sees "every race," he said. "It's not like, just the white kids sitting at one table or black kids at one table."

Maliki is set to graduate from Metropolitan Learning Center in Bloomfield this spring. Metropolitan is one of Connecticut's 84 magnet schools designed to bring together students from different socioeconomic backgrounds. These magnet schools make Connecticut a rare exception in a region that increasingly accepts racially isolated schools as inevitable.

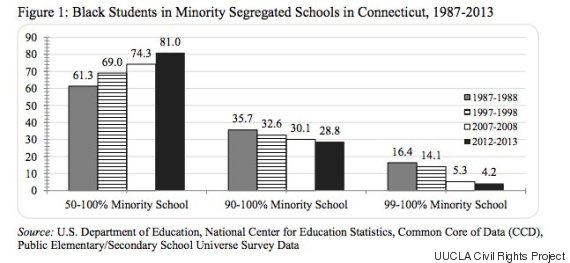

"It is the only state in the Northeast that is going in a positive direction and it has created voluntary processes that have clearly reduced severe segregation in a time devoid of national leadership," an April report from UCLA's Civil Rights Project found. "This is a solid accomplishment that the state should be proud of and other states should look at as an example."

Sunday marks the 61st anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, the case that declared intentionally segregated schools unconstitutional and set off a wave of efforts to increase school diversity. For years following the case, court-ordered interventions boosted school integration. However, since a string of court decisions allowed states to relax these efforts, the number of students in intensely segregated schools has risen since the late '80s and '90s.

Connecticut stands as a unique deviation from this trend. In 1996, a decision in the state's Supreme Court in a case called Sheff v. O'Neill ruled that "racial and ethnic segregation has a pervasive and invidious impact on schools," and ordered the governor and state legislature to find a solution. In 2003 the legislature created a system to fund regional magnet schools and a voluntary interdistrict transfer system.

The transfer system allows a small number of urban students to attend suburban schools and vice versa -- something atypical in traditional public schools, where students usually live close to the school they attend. The magnet schools draw from students in both urban and suburban districts through a lottery.

About 40,000 Connecticut students currently attend a regional magnet school, according to the UCLA report. In 1987, about 16.4 percent of black students in the state attended schools that were nearly 100 percent minority. Now, about 4.2 percent of black students do.

Maliki attends one of 19 magnets schools managed by Connecticut's Capitol Region Education Council. Overall, CREC schools serve a population that is32 percent white, 28 percent black and 27 percent Hispanic. Some 48 percent of CREC students are eligible for free and reduced price lunch.Connecticut Makes Rare Progress On School Segregation As America Moves Backwards: