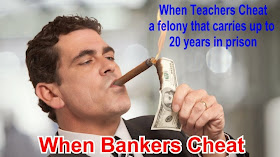

If you cheat to escape a corrupt accountability system, who is really to blame?

An Atlanta jury last week convicted 11 teachers of racketeering in a standardized test-cheating scandal. Yes, prosecutors used a law previously employed against mobsters against the educators, who were part of a group of 35 indicted in 2013 in the scheme. That included the now-deceased Atlanta schools superintendent, Beverly Hall. You can read here about how and why the cheating scheme occurred in Atlanta. The following post looks at something broader: how the scandal fits into a story about the consequences of bad policy-making. When people cheat to escape a corrupt accountability system, who is to blame?

This was written by scholar Richard Rothstein, a research associate at theEconomic Policy Institute, a non-profit created in 1986 to broaden the discussion about economic policy to include the interests of low- and middle-income workers. He is also senior fellow of the Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Law and Social Policy at the University of California (Berkeley) School of Law, and he is the author of books including “Grading Education: Getting Accountability Right, and “Class and Schools: Using Social, Economic and Educational Reform to Close the Black-White Achievement Gap.” He was a national education writer for The New York Times as well. This appeared on the EPI website and I am republishing it with permission.

By Richard Rothstein

Eleven Atlanta educators, convicted and imprisoned, have taken the fall for systematic cheating on standardized tests in American education. Such cheating is widespread, as is similar corruption in any institution—whether health care, criminal justice, the Veterans Administration, or others—where top policymakers try to manage their institutions with simple quantitative measures that distort the institution’s goals. This corruption is especially inevitable when out-of-touch policymakers set impossible-to-achieve goals and expect that success will nonetheless follow if only underlings are held accountable for measurable results.

There was little doubt, even before the jury’s decision, that Atlanta teachers and administrators had changed answers on student test booklets to increase scores. There was also little doubt that Atlanta’s late superintendent, Beverly Hall, was partly responsible because she had, as a state investigation revealed, “created a culture of fear, intimidation and retaliation” that had permitted “cheating—at all levels—to go unchecked for years.”

What the trial did not explore was whether Dr. Hall herself was reacting to a culture of fear, intimidation, and retaliation that her board, state education officials, and the Bush and Obama administrations had created. Just as her principals’ jobs were in jeopardy if test scores didn’t rise, her tenure, too, was dependent on ever rising test scores.

Holding educators accountable for student test results makes sense if the tests are reasonable reflections of teacher performance. But if they are not, and if educators are being held accountable for meeting standards that are If you cheat to escape a corrupt accountability system, who is really to blame? - The Washington Post: