Strict rules have helped boost academic performance in New Orleans, but some schools go too far

School was a complete joke to me as a young child. I thought it was just a place where I could come and socialize, play around, eat the free lunch and wander up and down the halls. There was a time in the third grade when I listened to James Brown music and danced to it while the other students reviewed nouns. This type of behavior led to my having to repeat the fourth grade. In my own way, I contributed to New Orleans’low academic performance prior to Hurricane Katrina.

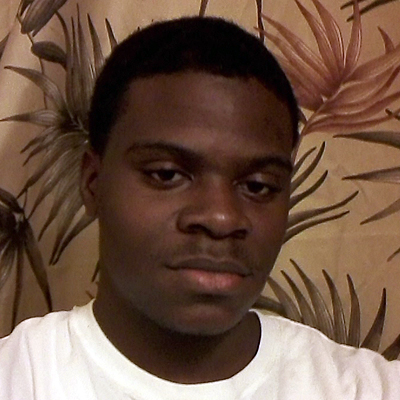

Merlin George graduated this spring from New Orleans’ Lake Area New Tech Early College High School. He will attend the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in the fall.

Before Katrina, New Orleans schools were among the nation’s worst when it came to graduation rates, standardized test scores, and other measurements. Partly for this reason, the Recovery School District (RSD) took over most public schools in New Orleans after the storm.

Most RSD schools have been very strict— much stricter than the old schools I attended as a young child. Overall, I think this has helped students progress, although sometimes I worry that some schools go too far. Not only did the RSD take over most schools after Hurricane Katrina, but all of the system’s teachers were fired. The schools started hiring more teachers through Teach for America, which recruits recent college graduates to teach for at least two years in low-income schools. These are mostly white teachers from elite colleges and universities across the country who help enforce the new style of discipline in New Orleans schools.

Under the new approach, schools have implemented policies controlling which accessories (hats, jewelry, etc.) are acceptable to wear, along with strict school-uniform codes. Students are restricted from wearing certain color socks, shoes, hair colors, and excessive jewelry. We also can’t wear certain hair designs (including dreadlocks and natural afros), clothing that doesn’t have a school name on it, and we are limited to specific types of backpacks. These rules are helpful at maintaining order, but I question whether they are necessary in the long-term.

STUDENT VOICES:

NEW ORLEANS PERSPECTIVES

This essay is part of a collaboration betweenThe Hechinger Report and high school students at Bard’s Early College in New Orleans. The teenagers wrote opinion pieces on whether all students should be encouraged to attend college, the value of alternative teacher preparation programs such as Teach For America, the importance of desegregation, or the best approach to school discipline.

The accessories we wear with our uniforms won’t determine how successful we will be in life. The color of our socks or shoes won’t determine whether we will get into college. And learning how to walk in a straight line, as required by many charter schools, won’t determine whether we know how to behave as adults. Too much focus on monitoring students in the hallway and sitting up straight in class is unnecessary because its takes the focus away from books and learning.

We all know that rules and regulations are placed in a school to ensure order, which is important. But cutting down on some of rules would mean that students wouldn’t have to spend so much time worrying about being stopped every Strict rules have helped boost academic performance in New Orleans, but some schools go too far | Hechinger Report:

Q & A with Dick Molpus: Anatomy of historic apology for hometown’s racist and violence past on eve of Freedom Summer anniversary

Mississippi’s former Democratic Secretary of State Dick Molpus, born and raised in Neshoba County, stood up 25 years ago at the Mount Zion Church in his hometown of Philadelphia and officially apologized to the families of the three slain civil rights workers murdered when they came to help blacks register to vote. In 1989, some 25 years after the murders, Dick Molpus became the only public offici